What Diseases Do Humans Give Zoo Animals

| Zoonosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Zoönosis |

| |

| A canis familiaris with rabies. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Communicable diseases |

A zoonosis (plural zoonoses, or zoonotic diseases) is an infectious disease caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a bacterium, virus, parasite or prion) that has jumped from an brute (usually a vertebrate) to a human being.[1] [2] [three] Typically, the first infected human transmits the infectious agent to at to the lowest degree 1 other human, who, in plough, infects others.

Major mod diseases such as Ebola virus disease and salmonellosis are zoonoses. HIV was a zoonotic disease transmitted to humans in the early on role of the 20th century, though information technology has now mutated to a dissever homo-only disease.[4] [5] [6] Most strains of influenza that infect humans are human diseases, although many strains of bird flu and swine influenza are zoonoses; these viruses occasionally recombine with man strains of the flu and tin can cause pandemics such as the 1918 Castilian flu or the 2009 swine flu.[7] Taenia solium infection is one of the neglected tropical diseases with public health and veterinary concern in endemic regions.[8] Zoonoses can be caused past a range of illness pathogens such as emergent viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites; of 1,415 pathogens known to infect humans, 61% were zoonotic.[9] Most human being diseases originated in animals; yet, but diseases that routinely involve not-homo to homo transmission, such equally rabies, are considered direct zoonoses.[10]

Zoonoses take different modes of transmission. In direct zoonosis the illness is directly transmitted from animals to humans through media such as air (influenza) or through bites and saliva (rabies).[11] In dissimilarity, transmission can also occur via an intermediate species (referred to as a vector), which carry the disease pathogen without getting ill. When humans infect animals, it is called opposite zoonosis or anthroponosis.[12] The term is from Greek: ζῷον zoon "fauna" and νόσος nosos "sickness".

Host genetics plays an important function in determining which animal viruses will be able to make copies of themselves in the homo body. Unsafe animal viruses are those that require few mutations to begin replicating themselves in human cells. These viruses are unsafe since the required combinations of mutations might randomly ascend in the natural reservoir.[xiii]

Causes [edit]

The emergence of zoonotic diseases originated with the domestication of animals.[xiv] Zoonotic transmission can occur in any context in which there is contact with or consumption of animals, fauna products, or animal derivatives. This can occur in a companionistic (pets), economical (farming, trade, butchering, etc.), predatory (hunting, butchering or consuming wild game) or research context.[ commendation needed ]

Recently, there has been a rise in frequency of appearance of new zoonotic diseases. "Approximately 1.67 1000000 undescribed viruses are thought to exist in mammals and birds, up to half of which are estimated to have the potential to spill over into humans," says a study[xv] led past researchers at the University of California, Davis. Co-ordinate to a report from the United Nations Environment Programme and International Livestock Research Institute large part of the causes are environmental like climate modify, unsustainable agriculture, exploitation of wildlife, country use modify. Others are linked to changes in human society like more than mobility. The organizations propose a set of measures to stop the rise.[16] [17]

Contagion of food or water supply [edit]

The near significant zoonotic pathogens causing foodborne diseases are Escherichia coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Caliciviridae, and Salmonella.[18] [19] [20]

In 2006 a briefing held in Berlin focused on the issue of zoonotic pathogen effects on nutrient safety, urging authorities intervention and public vigilance against the risks of catching food-borne diseases from farm-to-tabular array dining.[21]

Many nutrient-borne outbreaks can be linked to zoonotic pathogens. Many different types of nutrient that have an animal origin can become contaminated. Some common nutrient items linked to zoonotic contaminations include eggs, seafood, meat, dairy, and even some vegetables.[22]

Outbreaks involving contaminated nutrient should be handled in preparedness plans to preclude widespread outbreaks and to efficiently and effectively contain outbreaks.[23]

Farming, ranching and fauna husbandry [edit]

Contact with subcontract animals can lead to affliction in farmers or others that come into contact with infected farm animals. Glanders primarily affects those who work closely with horses and donkeys. Close contact with cattle tin can pb to cutaneous anthrax infection, whereas inhalation anthrax infection is more common for workers in slaughterhouses, tanneries and wool mills.[24] Close contact with sheep who have recently given nativity can lead to infection with the bacterium Chlamydia psittaci, causing clamydiosis (and enzootic abortion in significant women), as well as increment the risk of Q fever, toxoplasmosis, and listeriosis, in the meaning or otherwise immunocompromised. Echinococcosis is caused by a tapeworm, which tin can spread from infected sheep by food or water contaminated by feces or wool. Bird influenza is common in chickens and, while rare in humans, the main public wellness worry is that a strain of bird flu volition recombine with a human flu virus and crusade a pandemic like the 1918 Spanish flu. In 2017, gratis-range chickens in the UK were temporarily ordered to remain inside due to the threat of bird influenza.[25] Cattle are an important reservoir of cryptosporidiosis,[26] which mainly affects the immunocompromised. Reports have shown mink can too get infected.[27] In Western countries, Hepatitis E burden is largely dependent on exposure to animal products, and pork is a significant source of infection, in this respect.[28]

Veterinarians are exposed to unique occupational hazards when it comes to zoonotic disease. In the US, studies have highlighted an increased chance of injuries and lack of veterinary awareness of these hazards. Research has proved the importance for continued clinical veterinarian education on occupational risks associated with musculoskeletal injuries, animal bites, needle-sticks, and cuts.[29]

A July 2020 written report past the United Nations Environment Programme stated that the increment in zoonotic pandemics is directly owing to anthropogenic devastation of nature and the increased global demand for meat, and that the industrial farming of pigs and chickens in particular will exist a principal gamble gene for the spillover of zoonotic diseases in the time to come.[xxx]

Wildlife trade or animal attacks [edit]

The wildlife trade may increase spillover risk considering information technology directly increases the number of interactions across beast species, sometimes in small spaces.[31] The origin of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic[32] [33] is traced to the wet markets in China.[34] [35] [36]

- Rabies

Insect vectors [edit]

- African sleeping sickness

- Dirofilariasis

- Eastern equine encephalitis

- Japanese encephalitis

- Saint Louis encephalitis

- Scrub typhus

- Tularemia

- Venezuelan equine encephalitis

- Westward Nile fever

- Western equine encephalitis

- Zika fever

Pets [edit]

Pets tin can transmit a number of diseases. Dogs and cats are routinely vaccinated against rabies. Pets can as well transmit ringworm and Giardia, which are endemic in both animal and human populations. Toxoplasmosis is a mutual infection of cats; in humans it is a mild disease although it tin can be dangerous to pregnant women.[37] Dirofilariasis is acquired past Dirofilaria immitis through mosquitoes infected by mammals like dogs and cats. Cat-scratch disease is caused past Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana, which are transmitted by fleas that are endemic to cats. Toxocariasis is the infection of humans by any of species of roundworm, including species specific to dogs (Toxocara canis) or cats (Toxocara cati). Cryptosporidiosis can be spread to humans from pet lizards, such as the leopard gecko. Encephalitozoon cuniculi is a microsporidial parasite carried by many mammals, including rabbits, and is an important opportunistic pathogen in people immunocompromised by HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, or CD4+ T-lymphocyte deficiency.[38]

Pets may also serve as a reservoir of viral disease and contribute to the chronic presence of sure viral diseases in the homo population. For example, approximately 20% of domestic dogs, cats and horses carry anti-Hepatitis E virus antibodies and thus these animals probably contribute to human Hepatitis E burden also.[39] For non-vulnerable populations (people who are not immunocompromised) the associated affliction burden is, nonetheless, small.[ commendation needed ]

Exhibition [edit]

Outbreaks of zoonoses have been traced to homo interaction with, and exposure to, other animals at fairs, alive animal markets,[40] petting zoos, and other settings. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an updated list of recommendations for preventing zoonosis transmission in public settings.[41] The recommendations, developed in conjunction with the National Clan of State Public Health Veterinarians,[42] include educational responsibilities of venue operators, limiting public creature contact, and animal care and management.

Hunting and bushmeat [edit]

- HIV

- SARS

Deforestation, biodiversity loss and ecology degradation [edit]

Kate Jones, Chair of Ecology and Biodiversity at University College London, says zoonotic diseases are increasingly linked to ecology alter and human being behaviour. The disruption of pristine forests driven past logging, mining, road building through remote places, rapid urbanisation and population growth is bringing people into closer contact with creature species they may never have been almost before. The resulting transmission of disease from wildlife to humans, she says, is now "a subconscious cost of human economic development".[43] In a guest article, published by IPBES, President of the EcoHealth Alliance and zoologist Peter Daszak, along with three co-chairs of the 2019 Global Cess Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Josef Settele, Sandra Díaz, and Eduardo Brondizio, wrote that "rampant deforestation, uncontrolled expansion of agriculture, intensive farming, mining and infrastructure development, as well as the exploitation of wild species have created a 'perfect storm' for the spillover of diseases from wildlife to people."[44]

Joshua Moon, Clare Wenham and Sophie Harman said that there is bear witness that decreased biodiversity has an issue on the diversity of hosts and frequency of man-fauna interactions with potential for pathogenic spillover.[45]

An April 2020 written report, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Club'south Office B journal, found that increased virus spillover events from animals to humans tin can be linked to biodiversity loss and environmental deposition, equally humans further encroach on wildlands to engage in agriculture, hunting and resource extraction they go exposed to pathogens which unremarkably would remain in these areas. Such spillover events take been tripling every decade since 1980.[46] An August 2020 report, published in Nature, concludes that the anthropogenic devastation of ecosystems for the purpose of expanding agriculture and man settlements reduces biodiversity and allows for smaller animals such every bit bats and rats, who are more adjustable to human being pressures and too conduct the virtually zoonotic diseases, to proliferate. This in turn can result in more pandemics.[47]

In October 2020, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published its study on the 'era of pandemics' by 22 experts in a variety of fields, and concluded that anthropogenic destruction of biodiversity is paving the way to the pandemic era, and could result in equally many every bit 850,000 viruses being transmitted from animals – in particular birds and mammals – to humans. The increased force per unit area on ecosystems is existence driven past the "exponential ascent" in consumption and trade of commodities such every bit meat, palm oil, and metals, largely facilitated by developed nations, and past a growing man population. Co-ordinate to Peter Daszak, the chair of the grouping who produced the report, "there is no neat mystery nigh the cause of the Covid-xix pandemic, or of any modern pandemic. The same man activities that drive climatic change and biodiversity loss besides bulldoze pandemic take a chance through their impacts on our environment."[48] [49] [50]

Climate modify [edit]

According to a report from the United nations Surroundings Programme and International Livestock Research Institute, entitled "Preventing the next pandemic – Zoonotic diseases and how to break the chain of transmission," climate change is one of the vii human-related causes of the increase in the number of zoonotic diseases.[16] [17] The University of Sydney issued a study, in March 2021, that examines factors increasing the likelihood of epidemics and pandemics similar the COVID-19 pandemic. The researchers found that "pressure level on ecosystems, climate alter and economical development are primal factors" in doing and then. More zoonotic diseases were establish in high-income countries.[51]

In 2022, a big study dedicated to the link between climate change and Zoonosis was published. The study institute a potent link between climatic change and the epidemic emergence in the concluding fifteen years, equally information technology caused a massive migration of species to new areas, and consequently contact between species which do not normally come in contact with one another. Even in a scenario with weak climatic changes, there will exist 15,000 spillover of viruses to new hosts in the next decades. The areas with the near possibilities for spillover are the mountainous tropical regions of Africa and southeast Asia. Southeast Asia is especially vulnerable as it has a large number of bat species that generally do not mix, but could easily if climate change forced them to begin migrating.[52]

A 2021 report found possible links between climate change and transmission of COVID-19 through bats. The authors propose that climate-driven changes in the distribution and robustness of bat species harboring coronaviruses may have occurred in eastern Asian hotspots (southern Prc, Myanmar and Lao people's democratic republic), constituting a driver backside the evolution and spread of the virus.[53] [54]

Secondary transmission [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. You can assistance by adding to it. (August 2020) |

- Ebola and Marburg are examples of viral hemorrhagic disease.

History [edit]

During nigh of man prehistory groups of hunter-gatherers were probably very small. Such groups probably made contact with other such bands only rarely. Such isolation would have caused epidemic diseases to be restricted to any given local population, because propagation and expansion of epidemics depend on frequent contact with other individuals who have not nevertheless developed an adequate allowed response.[55] To persist in such a population, a pathogen either had to be a chronic infection, staying present and potentially infectious in the infected host for long periods, or information technology had to have other additional species as reservoir where information technology can maintain itself until farther susceptible hosts are contacted and infected.[56] [57] In fact, for many "human" diseases, the human is actually better viewed equally an accidental or incidental victim and a dead-end host. Examples include rabies, anthrax, tularemia and West Nile virus. Thus, much of man exposure to communicable diseases has been zoonotic.[58]

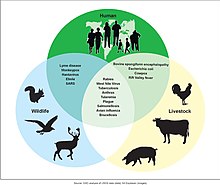

Possibilities for zoonotic disease transmissions

Many diseases, fifty-fifty epidemic ones, have zoonotic origin and measles, smallpox, flu, HIV, and diphtheria are detail examples.[59] [60] Various forms of the common cold and tuberculosis likewise are adaptations of strains originating in other species.[ citation needed ] Some experts accept suggested that all human being viral infections were originally zoonotic.[61]

Zoonoses are of interest because they are often previously unrecognized diseases or have increased virulence in populations defective amnesty. The West Nile virus kickoff appeared in the Usa in 1999, in the New York City area. Bubonic plague is a zoonotic disease,[62] as are salmonellosis, Rocky Mount spotted fever, and Lyme disease.

A major factor contributing to the appearance of new zoonotic pathogens in human being populations is increased contact betwixt humans and wildlife.[63] This tin be caused either by encroachment of human activity into wilderness areas or by movement of wild fauna into areas of human being activity. An case of this is the outbreak of Nipah virus in peninsular Malaysia, in 1999, when intensive pig farming began within the habitat of infected fruit bats.[ citation needed ] The unidentified infection of these pigs amplified the strength of infection, transmitting the virus to farmers, and eventually causing 105 human being deaths.[64]

Similarly, in recent times avian influenza and W Nile virus have spilled over into human populations probably due to interactions between the carrier host and domestic animals.[ commendation needed ] Highly mobile animals, such as bats and birds, may present a greater risk of zoonotic transmission than other animals due to the ease with which they can move into areas of human dwelling house.

Because they depend on the human host for role of their life-cycle, diseases such as African schistosomiasis, river blindness, and elephantiasis are not divers as zoonotic, even though they may depend on manual by insects or other vectors.[ citation needed ]

Use in vaccines [edit]

The commencement vaccine against smallpox past Edward Jenner in 1800 was by infection of a zoonotic bovine virus which acquired a disease called cowpox.[65] Jenner had noticed that milkmaids were resistant to smallpox. Milkmaids contracted a milder version of the affliction from infected cows that conferred cantankerous immunity to the human affliction. Jenner abstracted an infectious preparation of 'cowpox' and subsequently used it to inoculate persons confronting smallpox. Every bit a result, smallpox has been eradicated globally, and mass vaccination against this disease ceased in 1981.[66] There are a variety of vaccine varieties, including traditional inactivated pathogen vaccines, Subunit vaccines, live attenuated vaccines. There are also new vaccine technologies such as viral vector vaccines and Deoxyribonucleic acid/RNA Vaccines, which includes the SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus vaccines.[67]

Lists of diseases [edit]

| Disease[68] | Pathogen(s) | Animals involved | Mode of transmission | Emergence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African sleeping sickness | Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense | range of wildlife and domestic livestock | transmitted by the seize with teeth of the tsetse fly | 'present in Africa for thousands of years' – major outbreak 1900–1920, cases go on (sub-Saharan Africa, 2020) |

| Angiostrongyliasis | Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Angiostrongylus costaricensis | rats, cotton rats | consuming raw or undercooked snails, slugs, other mollusks, crustaceans, contaminated water, and unwashed vegetables contaminated with larvae | |

| Anisakiasis | Anisakis | whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, other marine animals | eating raw or undercooked fish and squid contaminated with eggs | |

| Anthrax | Bacillus anthracis | commonly – grazing herbivores such as cattle, sheep, goats, camels, horses, and pigs | by ingestion, inhalation or peel contact of spores | |

| Babesiosis | Babesia spp. | mice, other animals | tick bite | |

| Baylisascariasis | Baylisascaris procyonis | raccoons | ingestion of eggs in feces | |

| Barmah Forest fever | Barmah Forest virus | kangaroos, wallabies, opossums | mosquito bite | |

| Bird influenza | Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 | wild birds, domesticated birds such equally chickens[69] | shut contact | 2003–xix Avian Influenza in Southeast Asia and Egypt |

| Bovine spongiform encephalopathy | Prions | cattle | eating infected meat | isolated like cases reported in ancient history; in recent Great britain history probable start in the 1970s[70] |

| Brucellosis | Brucella spp. | cattle, goats, pigs, sheep | infected milk or meat | historically widespread in Mediterranean region; identified early on 20th century |

| Bubonic plague, Pneumonic plague, Septicemic plague, Sylvatic plague | Yersinia pestis | rabbits, hares, rodents, ferrets, goats, sheep, camels | flea bite | Epidemics like Black Death in Europe around 1347–53 during the Late Eye Age, Third Plague Pandemic in China-Qing dynasty and Republic of india alone |

| Capillariasis | Capillaria spp. | rodents, birds, foxes | eating raw or undercooked fish, ingesting embryonated eggs in fecal-contaminated nutrient, water, or soil | |

| Cat-scratch illness | Bartonella henselae | cats | bites or scratches from infected cats | |

| Chagas disease | Trypanosoma cruzi | armadillos, Triatominae (kissing bug) | Contact of mucosae or wounds with carrion of kissing bugs. Accidental ingestion of parasites in food contaminated by bugs or infected mammal excretae. | |

| Clamydiosis / Enzootic abortion | Chlamydophila abortus | domestic livestock, particularly sheep | close contact with postpartum ewes | |

| COVID-19 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus two | suspected: bats, felines, raccoon dogs, minks. White-tailed deer[71] | respiratory transmission | COVID-19 pandemic; 2019–present; Ongoing pandemic |

| Creutzfeldt-Jacob affliction | PrPvCJD | cattle | eating meat from animals with Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) | 1996–2001: United Kingdom |

| Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever | Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever orthonairovirus | cattle, goats, sheep, birds, multimammate rats, hares | tick bite, contact with actual fluids | |

| Cryptococcosis | Cryptococcus neoformans | unremarkably – birds like pigeons | inhaling fungi | |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Cryptosporidium spp. | cattle, dogs, cats, mice, pigs, horses, deer, sheep, goats, rabbits, leopard geckos, birds | ingesting cysts from water contaminated with feces | |

| Cysticercosis and taeniasis | Taenia solium, Taenia asiatica, Taenia saginata | commonly – pigs and cattle | consuming h2o, soil or food contaminated with the tapeworm eggs (cysticercosis) or raw or undercooked pork contaminated with the cysticerci (taeniasis) | |

| Dirofilariasis | Dirofilaria spp. | dogs, wolves, coyotes, foxes, jackals, cats, monkeys, raccoons, bears, muskrats, rabbits, leopards, seals, sea lions, beavers, ferrets, reptiles | mosquito bite | |

| Eastern equine encephalitis, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Western equine encephalitis | Eastern equine encephalitis virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, Western equine encephalitis virus | horses, donkeys, zebras, birds | musquito seize with teeth | |

| Ebola virus disease (a haemorrhagic fever) | Ebolavirus spp. | chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, fruit bats, monkeys, shrews, wood antelope and porcupines | through torso fluids and organs | 2013–16; possible in Africa |

| Other haemorrhagic fevers (Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, Dengue fever, Lassa fever, Marburg viral haemorrhagic fever, Rift Valley fever[72]) | Varies – normally viruses | varies (sometimes unknown) – commonly camels, rabbits, hares, hedgehogs, cattle, sheep, goats, horses and swine | infection unremarkably occurs through direct contact with infected animals | 2019–xx dengue fever |

| Echinococcosis | Echinococcus spp. | ordinarily – dogs, foxes, jackals, wolves, coyotes, sheep, pigs, rodents | ingestion of infective eggs from contaminated food or water with carrion of an infected, definitive host or fur | |

| Fasciolosis | Fasciola hepatica, Fasciola gigantica | sheep, cattle, buffaloes | ingesting contaminated plants | |

| Foodborne illnesses (commonly diarrheal diseases) | Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Listeria spp., Shigella spp. and Trichinella spp. | animals domesticated for food production (cattle, poultry) | raw or undercooked food made from animals and unwashed vegetables contaminated with carrion | |

| Giardiasis | Giardia lamblia | beavers, other rodents, raccoons, deer, cattle, goats, sheep, dogs, cats | ingesting spores and cysts in nutrient and water contaminated with carrion | |

| Glanders | Burkholderia mallei. | horses, donkeys | directly contact | |

| Gnathostomiasis | Gnathostoma spp. | dogs, minks, opossums, cats, lions, tigers, leopards, raccoons, poultry, other birds, frogs | raw or undercooked fish or meat | |

| Hantavirus | Hantavirus spp. | deer mice, cotton fiber rats and other rodents | exposure to feces, urine, saliva or bodily fluids | |

| Henipavirus | Henipavirus spp. | horses, bats | exposure to feces, urine, saliva or contact with sick horses | |

| Hepatitis E | Hepatitis Due east virus | domestic and wild animals | contaminated food or water | |

| Histoplasmosis | Histoplasma capsulatum | birds, bats | inhaling fungi in guano | |

| HIV | SIV Simian immunodeficiency virus | Non-human primates | Claret | Immunodeficiency resembling human AIDS was reported in captive monkeys in the United states of america offset in 1983.[73] [74] [75] SIV was isolated in 1985 from some of these animals, convict rhesus macaques suffering from simian AIDS (SAIDS).[74] The discovery of SIV was made shortly afterward HIV-1 had been isolated every bit the crusade of AIDS and led to the discovery of HIV-2 strains in West Africa. HIV-ii was more similar to the and so-known SIV strains than to HIV-i, suggesting for the first time the simian origin of HIV. Further studies indicated that HIV-ii is derived from the SIVsmm strain found in sooty mangabeys, whereas HIV-1, the predominant virus found in humans, is derived from SIV strains infecting chimpanzees (SIVcpz) |

| Japanese encephalitis | Japanese encephalitis virus | pigs, water birds | musquito bite | |

| Kyasanur Woods affliction | Kyasanur Wood illness virus | rodents, shrews, bats, monkeys | tick bite | |

| La Crosse encephalitis | La Crosse virus | chipmunks, tree squirrels | mosquito bite | |

| Leishmaniasis | Leishmania spp. | dogs, rodents, other animals[76] [77] | sandfly bite | 2004 Afghanistan |

| Leprosy | Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium lepromatosis | armadillos, monkeys, rabbits, mice[78] | directly contact, including meat consumption. However, scientists believe nigh infections are spread human being to man.[78] [79] | |

| Leptospirosis | Leptospira interrogans | rats, mice, pigs, horses, goats, sheep, cattle, buffaloes, opossums, raccoons, mongooses, foxes, dogs | direct or indirect contact with urine of infected animals | 1616–20 New England infection: Present twenty-four hour period in the United States–Native Americans; Killed effectually xc–95% of (Native America) |

| Lassa fever | Lassa fever virus | rodents | exposure to rodents | |

| Lyme affliction | Borrelia burgdorferi | deer, wolves, dogs, birds, rodents, rabbits, hares, reptiles | tick seize with teeth | |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis | Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus | rodents | exposure to urine, feces, or saliva | |

| Melioidosis | Burkholderia pseudomallei | diverse animals | direct contact with contaminated soil and surface water | |

| Microsporidiosis | Encephalitozoon cuniculi | Rabbits, dogs, mice, and other mammals | ingestion of spores | |

| Middle Due east respiratory syndrome | MERS coronavirus | bats, camels | close contact | 2012–present: Saudi arabia |

| Monkeypox | Monkeypox virus | rodents, primates | contact with infected rodents, primates, or contaminated materials | |

| Nipah virus infection | Nipah virus (NiV) | bats, pigs | direct contact with infected bats, infected pigs | |

| Orf | Orf virus | goats, sheep | shut contact | |

| Powassan encephalitis | Powassan virus | ticks | tick bites | |

| Psittacosis | Chlamydophila psittaci | macaws, cockatiels, budgerigars, pigeons, sparrows, ducks, hens, gulls and many other bird species | contact with bird aerosol | |

| Q fever | Coxiella burnetii | livestock and other domestic animals such equally dogs and cats | inhalation of spores, contact with bodily fluid or faeces | |

| Rabies | Rabies virus | unremarkably – dogs, bats, monkeys, raccoons, foxes, skunks, cattle, goats, sheep, wolves, coyotes, groundhogs, horses, mongooses and cats | through saliva by biting, or through scratches from an infected beast | Variety of places like Oceanic, Due south America, Europe; Twelvemonth is unknown |

| Rat-bite fever | Streptobacillus moniliformis, Spirillum minus | rats, mice | bites of rats but also urine and mucus secretions | |

| Rift Valley fever | Phlebovirus | livestock, buffaloes, camels | musquito seize with teeth, contact with actual fluids, claret, tissues, animate effectually butchered animals or raw milk | 2006–07 Due east Africa outbreak |

| Rocky Mount spotted fever | Rickettsia rickettsii | dogs, rodents | tick bite | |

| Ross River fever | Ross River virus | kangaroos, wallabies, horses, opossums, birds, flying foxes | mosquito bite | |

| Saint Louis encephalitis | Saint Louis encephalitis virus | birds | mosquito bite | |

| Astringent astute respiratory syndrome | SARS coronavirus | bats, civets | close contact, respiratory aerosol | 2002–04 SARS outbreak; started in China |

| Smallpox | Variola virus | Possible Monkeys or horses | Spread to person to person quickly | The final cases was in 1977; WHO certified to Eradicated (for the world) in Dec 1979 or 1980. |

| Swine influenza | A new strain of the influenza virus endemic in pigs (excludes H1N1 swine flu, which is a man virus). | pigs | close contact | 2009–10; 2009 swine flu pandemic; The outbreak began in Mexico. |

| Taenia crassiceps infection | Taenia crassiceps | wolves, coyotes, jackals, foxes | contact with soil contaminated with carrion | |

| Toxocariasis | Toxocara canis, Toxocara cati | dogs, foxes, cats | ingestion of eggs in soil, fresh or unwashed vegetables or undercooked meat | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | cats, livestock, poultry | exposure to cat feces, organ transplantation, blood transfusion, contaminated soil, h2o, grass, unwashed vegetables, unpasteurized dairy products and undercooked meat | |

| Trichinosis | Trichinella spp. | rodents, pigs, horses, bears, walruses, dogs, foxes, crocodiles, birds | eating undercooked meat | |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium bovis | infected cattle, deer, llamas, pigs, domestic cats, wild carnivores (foxes, coyotes) and omnivores (possums, mustelids and rodents) | milk, exhaled air, sputum, urine, faeces and pus from infected animals | |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis | lagomorphs (type A), rodents (type B), birds | ticks, deer flies, and other insects including mosquitoes | |

| West Nile fever | Flavivirus | birds, horses | mosquito bite | |

| Zika fever | Zika virus | chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, monkeys, baboons | mosquito bite, sexual intercourse, blood transfusion and sometimes bites of monkeys | 2015–16 epidemic in the Americas and Oceanic |

Run across also [edit]

- Animal welfare#Animal welfare organizations – Well-existence of non-man animals

- Conservation medicine

- Cantankerous-species transmission – Manual of a pathogen between dissimilar species

- Emerging infectious disease – Infectious disease of emerging pathogen, frequently novel in its outbreak range or transmission style

- Foodborne disease – Illness from eating spoiled food

- Spillover infection – Occurs when a reservoir population causes an epidemic in a novel host population

- Wildlife disease

- Veterinary medicine – Deals with the diseases of animals, creature welfare, etc.

- Wild animals smuggling and zoonoses

- Listing of zoonotic primate viruses

References [edit]

- ^ a b "zoonosis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary . Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ WHO. "Zoonoses". Archived from the original on three January 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ "A glimpse into Canada'due south highest containment laboratory for fauna health: The National Centre for Strange Animal Diseases". scientific discipline.gc.ca. Government of Canada. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved sixteen August 2019.

Zoonoses are infectious diseases which jump from an animal host or reservoir into humans.

- ^ Sharp PM, Hahn BH (September 2011). "Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic". Common cold Jump Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 1 (1): a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. PMC3234451. PMID 22229120.

- ^ Faria NR, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Baele M, Bedford T, Ward MJ, et al. (October 2014). "HIV epidemiology. The early spread and epidemic ignition of HIV-1 in human populations". Science. 346 (6205): 56–61. Bibcode:2014Sci...346...56F. doi:ten.1126/science.1256739. PMC4254776. PMID 25278604.

- ^ Marx PA, Alcabes PG, Drucker E (June 2001). "Serial human passage of simian immunodeficiency virus by unsterile injections and the emergence of epidemic human immunodeficiency virus in Africa". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Serial B, Biological Sciences. 356 (1410): 911–920. doi:ten.1098/rstb.2001.0867. PMC1088484. PMID 11405938.

- ^ Scotch M, Brownstein JS, Vegso Due south, Galusha D, Rabinowitz P (September 2011). "Man vs. animal outbreaks of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic". EcoHealth. 8 (iii): 376–380. doi:10.1007/s10393-011-0706-x. PMC3246131. PMID 21912985.

- ^ Coral-Almeida One thousand, Gabriël S, Abatih EN, Praet Northward, Benitez W, Dorny P (6 July 2015). "Taenia solium Human Cysticercosis: A Systematic Review of Sero-epidemiological Data from Endemic Zones effectually the World". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. nine (7): e0003919. doi:ten.1371/journal.pntd.0003919. PMC4493064. PMID 26147942.

- ^ Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse ME (July 2001). "Hazard factors for man affliction emergence". Philosophical Transactions of the Majestic Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 356 (1411): 983–989. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.0888. PMC1088493. PMID 11516376.

- ^ Marx PA, Apetrei C, Drucker E (Oct 2004). "AIDS as a zoonosis? Confusion over the origin of the virus and the origin of the epidemics". Journal of Medical Primatology. 33 (5–6): 220–226. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00078.10. PMID 15525322.

- ^ "Zoonosis". Medical Dictionary. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved thirty January 2013.

- ^ Messenger AM, Barnes AN, Gray GC (2014). "Reverse zoonotic affliction transmission (zooanthroponosis): a systematic review of seldom-documented human biological threats to animals". PLOS 1. 9 (ii): e89055. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...989055M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089055. PMC3938448. PMID 24586500.

- ^ Warren CJ, Sawyer SL (April 2019). "How host genetics dictates successful viral zoonosis". PLOS Biology. 17 (4): e3000217. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000217. PMC6474636. PMID 31002666.

- ^ Nibert D (2013). Animate being Oppression and Human being Violence: Domesecration, Capitalism, and Global Conflict. Columbia University Press. p. v. ISBN978-0231151894.

- ^ Grange ZL, Goldstein T, Johnson CK, Anthony South, Gilardi Chiliad, Daszak P, et al. (Apr 2021). "Ranking the chance of animal-to-human spillover for newly discovered viruses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (15). doi:10.1073/pnas.2002324118. PMC8053939. PMID 33822740.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus: Fright over rise in animal-to-human diseases". BBC. 6 July 2020. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Preventing the next pandemic – Zoonotic diseases and how to break the concatenation of transmission". United nations Ecology Programm. United nations. 15 May 2020. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Humphrey T, O'Brien S, Madsen 1000 (July 2007). "Campylobacters equally zoonotic pathogens: a food production perspective". International Periodical of Nutrient Microbiology. 117 (three): 237–257. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.01.006. PMID 17368847.

- ^ Cloeckaert A (June 2006). "Introduction: emerging antimicrobial resistance mechanisms in the zoonotic foodborne pathogens Salmonella and Campylobacter". Microbes and Infection. 8 (seven): 1889–1890. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.12.024. PMID 16714136.

- ^ Murphy FA (1999). "The threat posed by the global emergence of livestock, food-borne, and zoonotic pathogens". Register of the New York Academy of Sciences. 894 (1): xx–27. Bibcode:1999NYASA.894...20M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08039.ten. PMID 10681965. S2CID 13384121.

- ^ Med-Vet-Net. "Priority Setting for Foodborne and Zoonotic Pathogens" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved five April 2008.

- ^ Abebe, Engidaw; Gugsa, Getachew; Ahmed, Meselu (29 June 2020). "Review on Major Food-Borne Zoonotic Bacterial Pathogens". Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2020: 4674235. doi:x.1155/2020/4674235. ISSN 1687-9686. PMC7341400. PMID 32684938.

- ^ "Issuing Foodborne Outbreak Notices | CDC". www.cdc.gov. eleven January 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Inhalation Anthrax". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "Avian flu: Poultry to be allowed outside under new rules". BBC News. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Lassen B, Ståhl M, Enemark HL (June 2014). "Cryptosporidiosis - an occupational risk and a disregarded affliction in Estonia". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 56 (ane): 36. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-56-36. PMC4089559. PMID 24902957.

- ^ "Mink institute to have coronavirus on two Dutch farms – ministry". Reuters. 26 April 2020. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 27 Apr 2020.

- ^ Li TC, Chijiwa K, Sera N, Ishibashi T, Etoh Y, Shinohara Y, et al. (Dec 2005). "Hepatitis E virus transmission from wild boar meat". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1958–1960. doi:x.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100350. PMC8606544. PMID 16485490.

- ^ Rood KA, Pate ML (January 2019). "Cess of Musculoskeletal Injuries Associated with Palpation, Infection Control Practices, and Zoonotic Disease Risks amidst Utah Clinical Veterinarians". Periodical of Agromedicine. 24 (1): 35–45. doi:x.1080/1059924X.2018.1536574. PMID 30362924. S2CID 53092026.

- ^ Carrington D (half dozen July 2020). "Coronavirus: earth treating symptoms, non cause of pandemics, says UN". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Glidden CK, Nova North, Kain MP, Lagerstrom KM, Skinner EB, Mandle L, et al. (October 2021). "Human-mediated impacts on biodiversity and the consequences for zoonotic disease spillover". Current Biological science. 31 (19): R1342–R1361. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.070. PMID 34637744. S2CID 238588772.

- ^ You lot 1000 (October 2020). "Changes of Red china's regulatory regime on commercial artificial breeding of terrestrial wildlife in time of COVID-19 outbreak and impacts on the futurity". Biological Conservation. Oxford Academy Press. 250 (3): 108756. doi:x.1093/bjc/azaa084. PMC7953978.

- ^ Blattner C, Coulter One thousand, Wadiwel D, Kasprzycka E (2021). "Covid-19 and Capital: Labour Studies and Nonhuman Animals – A Roundtable Dialogue". Creature Studies Journal. University of Wollongong. 10 (i): 240–272. doi:10.14453/asj.v10i1.ten. ISSN 2201-3008. Retrieved xix September 2021.

- ^ Sun J, He WT, Wang L, Lai A, Ji X, Zhai 10, et al. (May 2020). "COVID-19: Epidemiology, Evolution, and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 26 (five): 483–495. doi:x.1016/j.molmed.2020.02.008. PMC7118693. PMID 32359479.

- ^ "WHO Points To Wildlife Farms In Southern China As Probable Source Of Pandemic". NPR. 15 March 2021.

- ^ Maxmen A (April 2021). "WHO report into COVID pandemic origins zeroes in on beast markets, non labs". Nature. 592 (7853): 173–174. Bibcode:2021Natur.592..173M. doi:ten.1038/d41586-021-00865-8. PMID 33785930. S2CID 232429241.

- ^ Prevention, CDC – Centers for Affliction Control and. "Toxoplasmosis – General Data – Meaning Women". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 Nov 2015. Retrieved one April 2017.

- ^ Weese JS (2011). Companion creature zoonoses. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 282–84. ISBN978-0813819648.

- ^ Li Y, Qu C, Spee B, Zhang R, Penning LC, de Homo RA, et al. (2020). "Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence in pets in the Netherlands and the permissiveness of canine liver cells to the infection". Irish gaelic Veterinary Journal. 73: 6. doi:x.1186/s13620-020-00158-y. PMC7119158. PMID 32266057.

- ^ Chomel BB, Belotto A, Meslin FX (January 2007). "Wild fauna, exotic pets, and emerging zoonoses". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (ane): 6–11. doi:ten.3201/eid1301.060480. PMC2725831. PMID 17370509.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005). "Compendium of Measures To Prevent Disease Associated with Animals in Public Settings, 2005: National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians, Inc. (NASPHV)" (PDF). MMWR. 54 (RR–4): inclusive page numbers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 Dec 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "NASPHV – National Association of Public Health Veterinarians". www.nasphv.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ^ Vidal J (18 March 2020). "'Tip of the iceberg': is our devastation of nature responsible for Covid-19?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved xviii March 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (27 April 2020). "Halt destruction of nature or suffer even worse pandemics, say world's top scientists". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Moon J, Wenham C, Harman S (November 2021). "SAGO has a politics problem, and WHO is ignoring it". BMJ. 375: n2786. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2786. PMID 34772656. S2CID 244041854.

- ^ Shield C (16 April 2020). "Coronavirus Pandemic Linked to Devastation of Wildlife and World's Ecosystems". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 16 Apr 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (five August 2020). "Deadly diseases from wildlife thrive when nature is destroyed, study finds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 Baronial 2020. Retrieved seven Baronial 2020.

- ^ Woolaston One thousand, Fisher JL (29 October 2020). "Un report says up to 850,000 animate being viruses could exist caught by humans, unless we protect nature". The Conversation. Archived from the original on one November 2020. Retrieved 29 Oct 2020.

- ^ Carrington D (29 October 2020). "Protecting nature is vital to escape 'era of pandemics' – report". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 Oct 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Escaping the 'Era of Pandemics': experts warn worse crises to come; offer options to reduce hazard". EurekAlert!. 29 October 2020. Archived from the original on 17 Nov 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Factors that may predict next pandemic". ScienceDaily. University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved nineteen May 2021.

- ^ Yong, Ed (28 April 2022). "We Created the 'Pandemicene'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Beyer RM, Manica A, Mora C (May 2021). "Shifts in global bat diversity suggest a possible role of climate change in the emergence of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2". The Science of the Total Environment. 767: 145413. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.767n5413B. doi:ten.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145413. PMC7837611. PMID 33558040.

- ^ Bressan D. "Climate Alter Could Have Played A Role In The Covid-19 Outbreak". Forbes . Retrieved ix Feb 2021.

- ^ "Early Concepts of Disease". sphweb.bumc.bu.edu . Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Van Seventer, Jean Maguire; Hochberg, Natasha S. (2017). "Principles of Infectious Diseases:Transmission, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Control". International Encyclopedia of Public Health: 22–39. doi:x.1016/B978-0-12-803678-5.00516-6. ISBN9780128037089. PMC7150340.

- ^ Health (Usa), National Institutes of; Report, Biological Sciences Curriculum (2007). Understanding Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases. National Institutes of Wellness (U.s.).

- ^ Baum, Stephen M. (2008). "Zoonoses-With Friends Like This, Who Needs Enemies?". Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 119: 39–52. ISSN 0065-7778. PMC2394705. PMID 18596867.

- ^ Weiss, Robin A; Sankaran, Neeraja (eighteen January 2022). "Emergence of epidemic diseases: zoonoses and other origins". Faculty Reviews. xi: two. doi:10.12703/r/11-2. ISSN 2732-432X. PMC8808746. PMID 35156099.

- ^ Wolfe, Nathan D.; Dunavan, Claire Panosian; Diamond, Jared (May 2007). "Origins of major human infectious diseases". Nature. 447 (7142): 279–283. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..279W. doi:10.1038/nature05775. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC7095142. PMID 17507975.

- ^ Benatar D (September 2007). "The chickens come home to roost". American Journal of Public Wellness. 97 (9): 1545–1546. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.090431. PMC1963309. PMID 17666704.

- ^ Meerburg BG, Singleton GR, Kijlstra A (2009). "Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public wellness". Disquisitional Reviews in Microbiology. 35 (3): 221–270. doi:10.1080/10408410902989837. PMID 19548807. S2CID 205694138.

- ^ Daszak P, Cunningham AA, Hyatt AD (Feb 2001). "Anthropogenic environmental alter and the emergence of infectious diseases in wild fauna". Acta Tropica. 78 (two): 103–116. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00179-0. PMID 11230820.

- ^ Field H, Young P, Yob JM, Mills J, Hall L, Mackenzie J (April 2001). "The natural history of Hendra and Nipah viruses". Microbes and Infection. 3 (4): 307–314. doi:x.1016/S1286-4579(01)01384-iii. PMID 11334748.

- ^ "History of Smallpox | Smallpox | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 21 February 2021. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "The Spread and Eradication of Smallpox | Smallpox | CDC". 19 Feb 2019.

- ^ "Why vaccines matter in the fight against zoonotic diseases". world wide web.thepigsite.com . Retrieved seven June 2022.

- ^ Information in this table is largely compiled from: World Health Organisation. "Zoonoses and the Man-Animal-Ecosystems Interface". Archived from the original on vi Dec 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ "Bird flu (Avian flu) - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Dispensary.

- ^ Prusiner SB (May 2001). "Shattuck lecture--neurodegenerative diseases and prions". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (20): 1516–1526. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105173442006. PMID 11357156.

- ^ "Why Omicron-infected white-tailed deer pose an especially big adventure to humans". Fortune.

- ^ "Haemorrhagic fevers, Viral". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Letvin NL, Eaton KA, Aldrich WR, Sehgal PK, Blake BJ, Schlossman SF, et al. (May 1983). "Caused immunodeficiency syndrome in a colony of macaque monkeys". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the U.s. of America. 80 (9): 2718–2722. Bibcode:1983PNAS...80.2718L. doi:ten.1073/pnas.80.9.2718. PMC393899. PMID 6221343.

- ^ a b Daniel Physician, Letvin NL, King NW, Kannagi K, Sehgal PK, Hunt RD, et al. (June 1985). "Isolation of T-cell tropic HTLV-Three-like retrovirus from macaques". Science. 228 (4704): 1201–1204. Bibcode:1985Sci...228.1201D. doi:10.1126/science.3159089. PMID 3159089.

- ^ King NW, Hunt RD, Letvin NL (December 1983). "Histopathologic changes in macaques with an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)". The American Journal of Pathology. 113 (three): 382–388. PMC1916356. PMID 6316791.

- ^ "Parasites – Leishmaniasis". CDC. 27 February 2019. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Leishmaniasis". World Health Arrangement. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ a b Clark L. "How Armadillos Tin Spread Leprosy". Smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved xvi April 2017.

- ^ Shute N (22 July 2015). "Leprosy From An Armadillo? That's An Unlikely Peccadillo". NPR. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved xvi April 2017.

Bibliography [edit]

- Bardosh Yard (2016). One Health: Science, Politics and Zoonotic Illness in Africa. London: Routledge. ISBN978-1-138-96148-seven. .

- Crawford D (2018). Mortiferous Companions: How Microbes Shaped our History. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0198815440.

- Felbab-Brown V (6 October 2020). "Preventing the adjacent zoonotic pandemic". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Greger M (2007). "The human/animal interface: emergence and resurgence of zoonotic infectious diseases". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 33 (4): 243–299. doi:10.1080/10408410701647594. PMID 18033595. S2CID 8940310. Archived from the original on one Baronial 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- H. Krauss, A. Weber, Yard. Appel, B. Enders, A. v. Graevenitz, H. D. Isenberg, H. Thousand. Schiefer, W. Slenczka, H. Zahner: Zoonoses. Infectious Diseases Transmissible from Animals to Humans. third Edition, 456 pages. ASM Press. American Guild for Microbiology, Washington, D.C., 2003. ISBN 1-55581-236-8.

- González JG (2010). Infection Gamble and Limitation of Fundamental Rights past Animal-To-Human Transplantations. EU, Spanish and High german Law with Special Consideration of English Law (in German language). Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovac. ISBN978-3-8300-4712-4.

- Quammen D (2013). Spillover: Brute Infections and the Next Human Pandemic. ISBN978-0-393-34661-9.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zoonoses. |

| | Look up zoonosis in Wiktionary, the complimentary lexicon. |

- AVMA Collections: Zoonosis Updates

- WHO tropical diseases and zoonoses

- Detection and Forensic Analysis of Wildlife and Zoonotic Disease

- Publications in Zoonotics and Wildlife Illness

- A bulletin from nature: coronavirus. United nations Environment Programme

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoonosis

Posted by: yearbywartime.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Diseases Do Humans Give Zoo Animals"

Post a Comment